The Origins of Racism Against Chinese Immigrants Around the Globe

Mae Ngai looks at 19th-century Chinese migration and how those early experiences might explain the racism we see today.

Violence and racism against Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders is on the rise in the United States. Recent events can be linked to xenophobia and some politicians’ anti-China rhetoric around the COVID-19 pandemic. However, some of the recent acts of hate against Asian Americans can be traced to much deeper, historical roots of anti-Chinese sentiment in the United States.

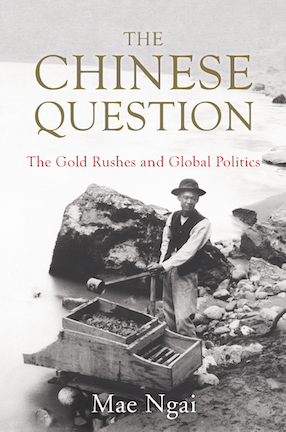

In her latest and timely book, The Chinese Question: The Gold Rushes and Global Politics, Mae Ngai, professor of Asian American studies and history and co-director of the Center for the Study of Ethnicity and Race, reveals the origins of prejudice against Chinese immigrants in the United States and the Anglophone world in the late-19th century. Ngai unravels misleading stereotypes about Chinese Americans, and Asian Americans in general, that have been perpetuated in academia for decades.

Columbia News met with Ngai to find out how the “coolie” myth came about, why we might be witnessing violence against Asian Americans today, and who she would invite to a dinner party.

Q: What inspired you to write your book, The Chinese Question: The Gold Rushes and Global Politics?

A: Some years ago, I was advising a student, who was writing a paper on California politics in the 19th century. The student wrote that Chinese were indentured laborers, or “coolies,” the antithesis of “free labor.” I had difficulty persuading them that they were wrong, because the “coolie” stereotype was entrenched in the historical literature. It was based on one scholar’s selective reading of testimonies before Congress, cherry-picked from 1,000-plus pages of diverse opinion. Subsequent histories repeated the same claim, and cited the same source. I doubt that anyone actually went back and read the original source or did any other research. The pattern showed both bias and laziness.

Q: What scholarship was missing (or incorrect) about Chinese immigrants in Anglo-American countries that you wanted to address in your book?

A: The “coolie” myth is insidious because it alleges that Chinese immigrants were pitiably oppressed, without individual personality or will, and pawns of big capitalists. Chinese were deemed a special, racialized version of “cheap labor,” which justified the Chinese exclusion laws.

Slaying the myth required both empirical and discursive analysis. In California, primary sources about Chinese, much less written by Chinese, are scarce. There are just a handful of local claims registers extant (which show that Chinese mining practices were much like those of Euro-Americans). In Australia, the colonial government and goldfield commissioners in Victoria kept records that are centrally preserved. In both places, I found testimonies by Chinese miners in courtrooms and inquest hearings. Comparative research yielded insights about common patterns in ownership, methods of work, and social organization.

Comparative work on the politics of Chinese exclusion in California, Australia, and South Africa also yielded important insights. There’s an assumption that anti-Chinese racism is a kind of generic idea, as though it exists already formed in a “cloud,” like an app that can be downloaded anywhere and at any time. My research revealed that anti-Chinese politics emerged in each location differently, according to different conditions. But politics also travel and borrow from each other, so that by the late-19th and early-20th centuries, there emerged a common racist theory grounded in white-settler colonialism. Chinese community leaders also spoke to local conditions, and also borrowed from each other’s arguments.

These patterns help us understand that racism is not a natural human response to people who are different (or, more accurately, who are construed as different). Rather, it is produced by politics. If we think about racism in this way, we can imagine and enable political alternatives.

Q: Sadly, we are witnessing a rise in violence and hatred against Asian Americans in the United States. How have previous laws that were enacted to prevent Chinese from immigrating to the U.S. impacted how Chinese Americans (and all Asian Americans) are treated today?

A: The exclusion laws codified the idea that Chinese were unassimilable and, therefore, would always be foreigners, even those born in the U.S. Although Congress repealed the exclusion laws in 1940s, the idea of permanent foreignness has had a very long shelf life. It was reproduced throughout the 20th century by the numerous wars conducted by the United States in Asia (U.S.-Philippine War, World War II, Korean War, Vietnam War).

All wars involve a dehumanization of the enemy, but in the case of Asians, there is a distinctive racial idiom, which alleges that Asians consider life cheap, and that they wage war in barbaric ways that require a like response. In our own time, economic and geopolitical competition with China has reproduced old stereotypes. Today’s “coolies” are factory workers in China’s special economic zones and Chinese and Chinese/Asian American university students—both are imagined as robots who work long hours without recompense or fun.

Q: Now that you’ve completed your book, hopefully you have time to read for pleasure. What are you reading and why?

A: This summer I am reading Viet Thanh Nguyen’s The Committed; Columbia Professor Claudio Lomnitz’s Nuestra America; Carribean Fragoza’s Eat the Mouth that Feeds You, Michael Lewis’s The Premonition, and Edward St. Aubyn’s Double Blind. I read a lot of thrillers, too, and read Stacey Abrams’s While Justice Sleeps.

Q: You're having a dinner party. Which three immigration activists, diplomats, poets, leaders, academics, or celebrities (alive or dead), would you invite, and why?

A: Frederick Douglass, who in 1869 opposed Chinese exclusion and advocated for free migration as a human right; Huang Zunxian, the Qing consul in San Francisco in the 1880s, who was also a poet; and Mohsin Hamid, whose novel Exit West imagines refugees navigating a strange but familiar world in the near future.

Check out Books to learn more about publications by Columbia professors.