A New Book Looks at the History of School Photos

Professor Marianne Hirsch on the afterlife of student pictures, enduring memories and what she is reading now.

Remember posing for school photos, that annual rite of passage back in elementary and middle school, both the individual and group shots, often set against a solid-color background? Days later, the prints would arrive discreetly in a white envelope and be either memorable or cringe-worthy.

School Photos in Liquid Time: Reframing Difference, a new book by Marianne Hirsch, the William Peterfield Trent Professor of English and Comparative Literature and a professor at the Institute for Research on Women, Gender and Sexuality, examines this common but overlooked genre of vernacular photography for the first time. Hirsch discusses the book (co-written with her husband, Leo Spitzer, a professor at Dartmouth) with Columbia News, as well as childhood memories, her 2020 reading list and where she likes to relax with a book.

Q. How did you come up with the idea for this book? Is there a personal connection?

A. The book emerges from the insight that the development of public schooling in various U.S. states and countries across the globe occurred around the same time as the development of photography, in the mid-to late-19th century. Schooling became a way to manage social differences in multicultural populations, and class photos could support that effort by emphasizing uniformity and minimizing disparities. School photos enable the creation of national and imperial subjects, but they can also create “others.” The book reveals multiple connections between the strategies of assimilation and integration, on one side, and persecution, exclusion, even genocide, on the other. Yet, in highlighting community, solidarity and the desire for learning, these images can also allow us to imagine justice and a more democratic future.

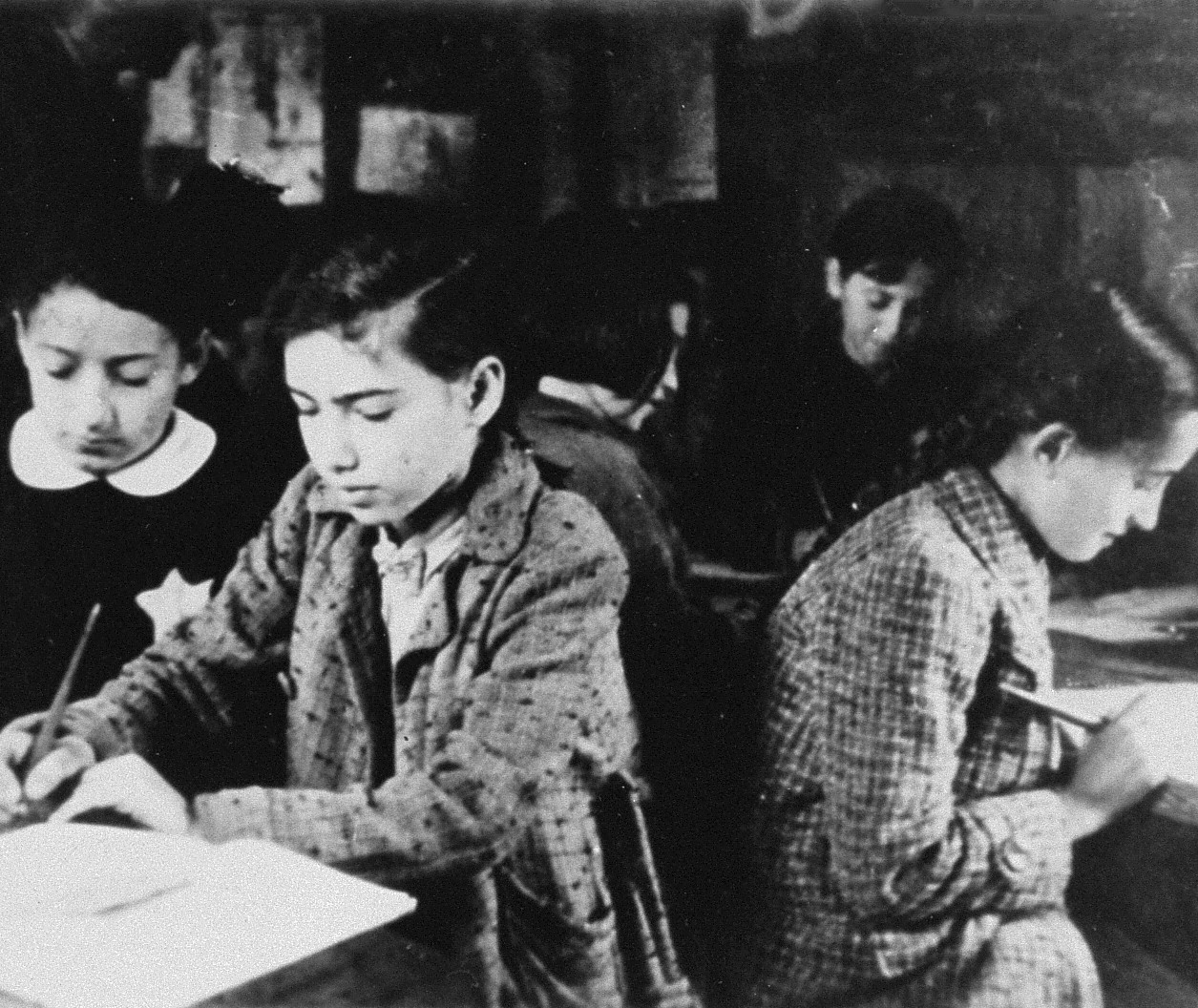

There is, indeed a personal connection. Both our families were assimilated Jews from parts of the Austro-Hungarian empire who embraced the promise of being accepted into the social mainstream. Education served as a vehicle for integration, and school photos from our relatives’ and their contemporaries’ childhoods in Vienna and Czernowitz up to the 1930s show integrated classrooms composed of students from different ethnic backgrounds. Of course, as these young people faced the camera, they did not know that a few years later some of them would be excluded, persecuted, deported, maybe killed—sometimes with the help of their classmates. In the book, this temporal incongruity is very poignant, both protecting the sense of a future these young subjects had, and being alert to the vulnerabilities and dangers they were facing.

The book places the history of Jewish assimilation, persecution and resistance into conversation with histories of colonial subjects in Africa, and with Native American, African American and Japanese American children in the United States.

Q. How does the accompanying exhibition at Dartmouth’s Hood Museum in Hanover, New Hampshire, (on view through April 12, 2020) amplify the book?

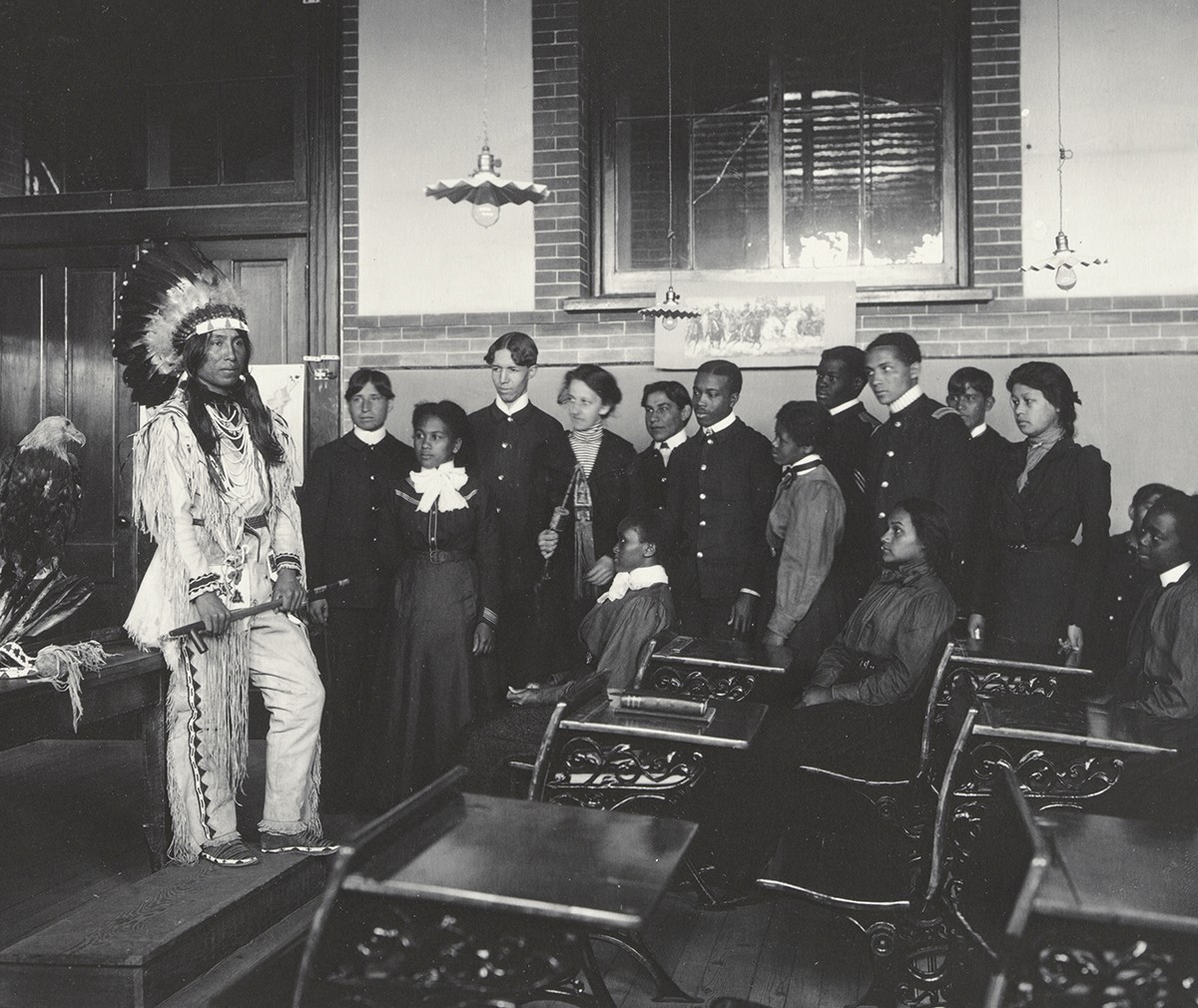

A. The aspect of the book that is most enhanced by the exhibition is the dialogue we stage between archival vernacular class pictures and the work of contemporary artists such as Vik Muniz and David Wojnarowicz, who reframe and comment on the photos. Several large works respond specifically to small, ordinary archival images, for example, a part of Carrie Mae Weems’ Hampton Project in which she enlarged Frances Benjamin Johnston’s early-20th-century photographs from the Hampton Normal and Agricultural School in Hampton, Virginia, a transformative boarding school for Native American and African American children. She printed them on mobile scrims that allow viewers to walk through the photos, undoing the fixity of the children’s Anglo-Europeanization.

Q. What do the book and school photos in general have to say about the educational opportunities offered to different groups of people?

A. The book confronts social inequalities and the unending struggles for equal opportunities in education for various vulnerable populations. For instance, an image from Daytona, Florida, taken in 1905, shows the noted educator Mary McLeod Bethune with a long, diagonal row of small African American girls lined up in their white blouses. Bethune started a school in a one-room house on a dirt road to compensate for the lack of adequate education for black children. The book prompts us to ask if things have really changed for certain populations.

Image Carousel with 5 slides

A carousel is a rotating set of images. Use the previous and next buttons to change the displayed slide

-

Slide 1: Mary McLeod Bethune with students from the Daytona (Florida) Literary and Industrial School for Training Negro Girls, about 1905.

-

Slide 2: "Class in American History," the Hampton Album; platinum print by Frances B. Johnson.

-

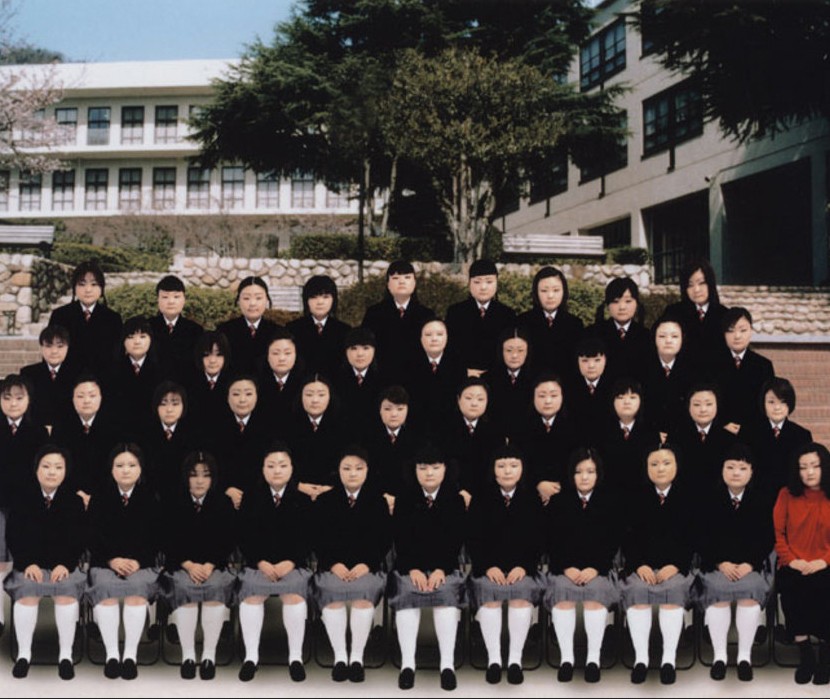

Slide 3: "School Days #1" by Tomoko Sawada, 2006; courtesy of the artist.

-

Slide 4: Clandestine school, Kovno ghetto, Lithuania, 1941-42.

-

Slide 5: "Mrs. Ziegler oversees her ninth-grade class at the internment camp in Jerome, Arkansas," 1942.

Mary McLeod Bethune with students from the Daytona (Florida) Literary and Industrial School for Training Negro Girls, about 1905.

"Class in American History," the Hampton Album; platinum print by Frances B. Johnson.

"School Days #1" by Tomoko Sawada, 2006; courtesy of the artist.

Clandestine school, Kovno ghetto, Lithuania, 1941-42.

"Mrs. Ziegler oversees her ninth-grade class at the internment camp in Jerome, Arkansas," 1942.

Q. Do you still have any of your school photos that you cherish?

A. Like most of us, I’m ambivalent about them. They evoke visceral feelings of desire and of abjection. Here I am: a subject of an institution—school— seen through the camera’s institutional gaze. I am a part of a cohort to which I both wanted and did not want to belong. But the photos also allow me to recall how much I loved, and indeed love, learning new things in the company of others.

Q. Much of your research has focused on memory. What does memory provide a window into?

A. My interest in memory emerged from my personal history as a child of Holocaust survivors, a history that’s made me especially attuned to how painful pasts are transmitted to future generations. What is our responsibility to what Susan Sontag has called “the pain of others?” The study of memory has been especially capacious for me as an interdisciplinary, transnational field of inquiry that offers a platform for bringing small stories and everyday lives to light that might otherwise remain hidden from history. My work has been motivated by the question of how memories of painful pasts might be mobilized for more hopeful futures. And by how memory can be a platform for progressive activism.

Q. What are some of your best and/or earliest memories?

A. I evoke one briefly in School Photos in Liquid Time. It’s my first day of school in Bucharest, Romania, where I grew up. I’m riding the streetcar with my mother, carrying a school bag, nervous about being left alone in a sea of strange kids. I spot a little girl with a white headband and two braids next to me and, looking up, I see that our mothers have started chatting. We are going to the same school! A friend! By the end of the day, I’m in tears. My new friend Gaby was placed in a different section of first grade. I’m on my own all day, but our mothers wait for us together. Gaby would be my best friend for five years, until I left Romania at age 12. We are in occasional touch still.

Q. What books are currently on your night table?

A. I tend to read books for projects—a new course, a book or article or review I’m writing. And, of course, books by friends and colleagues who I admire. I’m reading Mikhal Dekel’s moving family memoir Tehran Children, Hazel Carby’s transformational Imperial Intimacies: A Tale of Two Islands, Ariella Aïsha Azoulay’s magisterial Potential History: Unlearning Imperialism, Maria Stepanova’s Russian “meta-novel” After Memory I (or Post-Memory), currently only available in German translation, as well as several books on women and aging that I have been asked to review.

Q. What’s the last great book you read?

A. I am now reading material for a new course on refugees and stateless lives, which brought me to Valeria Luiselli’s beautiful Lost Children’s Archive.

Q. Describe your ideal reading experience (when, where, what, how).

A. I love reading outdoors in the shade of the lilac tree on the deck of my Vermont house, with some bird sounds in the background and my labradoodle Ziggy by my feet.

Q. What are you working on now?

A. I’m thinking about statelessness as a frame for responding both to the current crisis on our borders and the refugee crisis more broadly. I believe it’s vital for us to try to think beyond nations and nationalisms.