Nijinsky's Little-Known Sister Is the Subject of a New Book

Lynn Garafola's "La Nijinska" sheds light on a remarkably productive dancer and choreographer.

Overshadowed by her brother, dancer and choreographer Vaslav Nijinsky (1889-1950), Bronislava Nijinska had a far longer and more productive career, also as a choreographer and dancer. A creator of 20th-century neoclassicism, she produced her greatest work, Les Noces, under the influence of the Russian Revolution's avant-garde. Many of her ballets rested on the probing of gender boundaries, a mistrust of conventional gender roles, and the heightening of the ballerina's technical and artistic prowess. She worked with leading figures of 20th-century art, music, and ballet, including Igor Stravinsky, Sergei Diaghilev, Natalia Goncharova, Frederick Ashton, and Maria Tallchief.

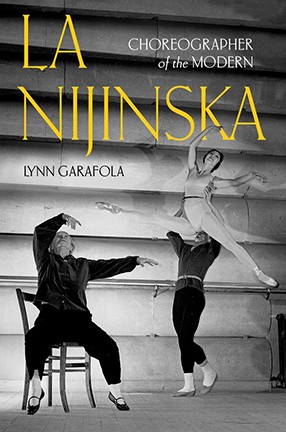

In La Nijinska: Choreographer of the Modern, the first biography of her, Lynn Garafola, professor emerita of dance at Barnard, sheds new light on Nijinska’s career, and on the history of ballet and modernism. The book also reveals the sexism pervasive in the upper echelons of the early-and-mid-20th-century ballet world, barriers that women choreographers still confront today.

Garafola discusses the book with Columbia News, along with what dance performances she’s planning to attend this spring, and why both La Nijinska and Sonia Sotomayor would make wonderful dinner companions.

Q. Why did you write this book?

A. I have wanted to tell Nijinska’s story since the 1980s when I read her book Early Memoirs, which ended before she turned 25, and saw a performance of her ballet, Les Noces, which overwhelmed me. Like Stravinsky’s score, the choreography was powerfully rhythmic and full of pathos, a Russian peasant wedding without folklore or joy. And, then, as I learned about additional ballets of hers, I was struck by the gender play in so many of them, and by the many male roles she crafted for herself. And to think I barely knew who she was.

Q. How is it that Vaslav Nijinsky is basically a household name, even to those not necessarily interested in ballet, while Nijinska, for all her accomplishments, is so little-known, especially to those outside the dance world?

A. Nijinsky was a once-in-a-lifetime talent, but his stardom was largely the work of others. Serge Diaghilev, who was his lover, built the entire repertory of the Ballets Russes around him, and did everything possible to advance his career as a brilliantly innovative choreographer. Nijinska, by contrast, was a woman, whose choreographic ambitions Diaghilev initially rejected, although after the Russian Revolution, which she had spent in Kyiv creating her first modern works, he engaged her as company choreographer.

By then, her brother was mentally ill, and would spend the rest of his life in and out of hospitals. Nijinsky’s wife, Romola, had no qualms about sensationalizing his tragedy in books that exalted him as a mad genius and the victim of Diaghilev’s Svengali-like behavior. After Stonewall, both men became gay heroes. Nijinsky’s life and legend left little space for a sister, however accomplished. It became a vicious circle: In order to talk about herself in Early Memoirs, Nijinska had to invoke her brother; it was the conundrum of Shakespeare’s sister.

Q. What do you think Nijinska would make of the state of women’s lives today, both in and beyond the dance world, especially in light of the women’s movement, feminism, and the Me Too movement?

A. I think she would be thrilled about the strides that women have made, but would note the barriers they still face as ballet choreographers. From the moment Nijinska left Soviet Russia in 1921, she fought for compensation that would enable her to support her mother and two children. One of the reasons she was considered “difficult” is that she demanded financial remuneration commensurate with her experience and responsibilities—even though she was routinely underpaid compared to male choreographers.

Nijinska would certainly have applauded the efforts by women to shatter the glass ceiling, thereby opening traditionally restricted jobs, and to challenge traditional definitions of femininity and female beauty. Finally, I think she would also have applauded the Me Too movement’s critique of sexual politics, something that flourished in the ballet world, but that she scrupulously avoided.

Q. What do you read when you’re working on a book? And what kind of reading do you avoid while writing?

A. When I’m working on a book, I continue to conduct research, because the writing itself opens new vistas or poses new questions that I need to investigate. However, when it comes to fiction, I seldom read anything new, but reread books I know so well they can lull me to sleep, even though I’m aware of verbal echoes and phrases.

When I write, I often listen to music, sometimes because it produces a certain mood, sometimes because of its rhythm. Music and movement are very close, and I have the sense at times that, thanks to music, writing can be a form of dancing.

Q. Have you been going to live dance performances during the pandemic? If so, what are you looking forward to this spring, both in person and online?

A. I started to go to live indoor performances last fall, and, like so many others, experienced a feeling of enormous gratitude to the dancers who were risking themselves day after day for us. Long before that, I was going to museums, and, again, I felt hugely indebted to everyone who made my visits possible. This spring, I’m looking forward to the New York City Ballet and to the Paul Taylor Dance Company, now directed by former Columbia student Michael Novak. In the summer, I’ll attend performances at Jacob’s Pillow in the Berkshires.

Online highlights have included Kyle Abraham’s When We Fell, a beautiful piece recorded on the Promenade of the New York State Theater (as we old-timers still call Lincoln Center’s David H. Koch Theater) with a diverse group of young New York City Ballet dancers; and some of the short pieces produced by the Guggenheim Museum’s Works & Process series when live performances went on hiatus. I also loved the dances on a carpet choreographed by Gabrielle Lamb in parks up and down the West Side.

Q. You’re hosting a dinner party. Which three academics or scholars, dead or alive, would you invite, and why?

A. I’d love to host a dinner party with Nijinska, Supreme Court Justice Sonia Sotomayor, and St. Catherine of Alexandria, whose attributes are the pen and the wheel of martyrdom. All three overcame enormous difficulties to make their mark; they experienced triumphs as well as nadirs, and although St. Catherine—if she actually existed—came from Alexandrian nobility, both Nijinska and Sotomayor came from extremely modest backgrounds. All three were Catholic, but none—even the martyred St. Catherine—have anything to do with the diehard conservatism of today’s U.S. Catholic hierarchy.

I would like to walk back in time with Sotomayor, who grew up, as I did, in a working-class New York neighborhood as part of an extended Catholic family. I would also like to know about the encounters that, like the Muse’s fatal kiss in the ballet Le Baiser de la Fée, marked the dawn of their creative or intellectual self-awareness, the moment of their birth as remarkable women.

Check out Books to learn more about publications by Columbia professors.