The Original It Girl’s Remarkable Life Is Chronicled in a New Biography

Professor Hilary Hallett turns the saga of pioneering writer-director Elinor Glyn into a subject of serious study.

Unlike typical romances, which end with wedding bells, the story of Elinor Glyn (1864–1943) began after her marriage foundered. Like most Victorian women, she aspired only to a good match. But when her husband, Clayton Glyn, gambled their fortune away, she turned to writing, and boldly challenged the era’s sexually straightjacketed literary code with her notorious bestseller, Three Weeks (1907), an erotic tale about an unhappily married woman’s sexual education of her young lover.

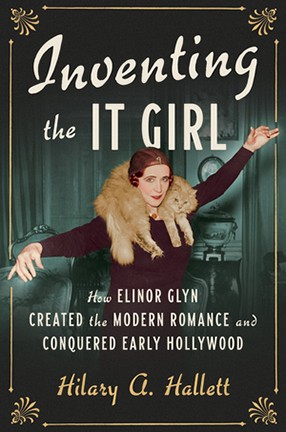

In Inventing the It Girl: How Elinor Glyn Created the Modern Romance and Conquered Early Hollywood, Hilary Hallett, professor of history and Mendelson Family Professor of American Studies, traces Glyn’s meteoric rise from a depressed British society darling to a renowned celebrity author who consorted with world leaders from St. Petersburg to Cairo to New York; reported from the trenches during World War I; and ended up in Los Angeles during the 1920s, where she became a successful screenwriter and director, and coined the term “It Girl.”

Hallett discusses the book with Columbia News, as well as what Glyn might make of today’s Hollywood and the Me Too movement, and who, along with Glyn, she would invite to a dinner party.

How did you come up with the idea for this book?

I became interested in the life of Glyn while researching my dissertation, which became my first book, Go West, Young Women! The Rise of Early Hollywood. Glyn was one of the few unfamiliar people I encountered when I began the research—and suddenly, she was everywhere I turned!

When I looked at the existing scholarly or popular histories, I found that most people treated her like a joke. Now I think this was because she was female, and genuinely quite eccentric and older. Glyn was 56 when she arrived in Hollywood in 1920, which made her virtually the oldest person working in the film industry at that time. Yet, the primary sources I was reading made it clear that this middle-aged writer—who had never seen a movie before she got to California—had amassed a tremendous amount of influence in this new industry very quickly. That contradiction intrigued me, as well as the fact that she aged into ever greater power, an almost unheard-of arc at that time for stories about women. She struck me at once as someone whose life illustrated the important role women played—as creators and audiences—in the ascent of what got called mass culture.

When I started to dig into her background, I realized that the press had downplayed what an interesting life she had led before she arrived in Los Angeles. Glyn had been ostracized from the aristocratic British society into which she had married for her scandalous sex novel, Three Weeks. But rather than retire in shame, she did something that no female writer had ever done: She used her notoriety to become a celebrity author, who grew so famous that she was one of the few women allowed to report from the trenches during World War I.

Flash forward almost 10 years after completing my dissertation, when my family spent a summer in Oxford so I could do some preliminary research in Glyn’s archive at Reading University to determine if I wanted to write her biography. Her archive at Reading is rich concerning her professional life, but short on the kinds of sources that would give access to what lay behind her professional persona. I did not want to attempt a biography without some access to her inner life. So I began writing to every remaining descendant of hers that I could find to see if any of her correspondence or diaries survived somewhere. Just when I was about to give up—two weeks before we were set to return to New York—an email arrived from her great-granddaughter, telling me she had a trunk in Wales filled with Glyn’s letters and diaries.

What do you think Glyn would make of the world today, especially in terms of Hollywood and the Me Too movement?

She was a woman with great vision, who called motion pictures the most important invention since the printing press. She admired the talent and ambition of those working in early Hollywood. And, by the 1910s, she saw that America was taking the reins from Britain in terms of imperial power and cultural prestige. So Glyn would not have been surprised to learn that Hollywood endured as a global media power, which influenced the development of so many other national cinemas.

In terms of the industry’s sexual politics, it’s important to note that Glyn was just one of many white women who wielded influence behind the camera in early Hollywood. When she arrived, there were more female directors at Universal Studios alone than there would be in the entire American film industry almost a century later. This was also the moment in which suffrage for women finally become a reality in many places, including the U.K. and the U.S., outside the South. There were examples everywhere of women breaking barriers.

But white women’s unusual influence was definitely on the wane by the time Glyn left Los Angeles in 1929. She also wrote a number of articles in the 1920s that indicated she was worried that there was a backlash developing over what she viewed as the remarkable advances in women’s equality with men. So I think she would have been saddened, but not surprised, to learn that opportunities for sexual exploitation became rife (as they were in virtually all other industries, it is important to recognize) once Hollywood became entirely male-dominated.

Are there are any classic novels that you have only recently read for the first time?

I worked my way through so much fiction during my twenties that there are not many classics I wish to read that I have not already read. But one classic I love and recently reread is Virginia Woolf’s To the Lighthouse.

Any great books or movies that you would recommend, and why?

Since I am in part a film historian, I am going to go with a film from the past: The Best Years of Our Lives (1945). This movie about the reintegration of three soldiers returning from World War II never fails to make me cry—and I have seen it at least a dozen times. Its brilliant writing, acting, and composition convey the cultural dynamics at work so well in that incredibly transitional moment that I always find myself sympathizing with all the characters. This, even when as a gender historian, I can also see how the movie offers a roadmap for why women’s progress in society would be rolled back, and heteronormativity would become more enshrined than ever before.

Which subjects do you wish more authors would write about?

Again, as a gender historian, I have to say the effects of pregnancy, childbirth, and young children on women’s lives. One of the chapters in my book tried to engage the effects of this on Glyn’s life directly. Until quite recently, the ability to get pregnant—with all the attendant risks and consequences—shaped women’s lives perhaps more than any other factor. I think that with the battle over reproductive freedom returning center stage in the U.S., we need to tell more stories that emphasize why control over your fertility is so crucial for anyone who can become pregnant.

What are you teaching this fall?

Since I am the new director of the Center for American Studies, I am teaching only one seminar in the spring—and it’s a favorite of mine— Gender History and American Film.

You're hosting a dinner party. Which authors or scholars, dead or alive, would you invite, and why?

That is easy: Elinor Glyn, James Baldwin, Joan Didion, and Simone de Beauvoir. Glyn was famous for her dinner parties and had a wicked sense of humor, so I would love to have met her. The other three predate this biography. Over the years, I have read and reread Baldwin’s and Didion’s books and essays more than any other nonfiction writers for lessons in style and substance. To me, no two authors have better captured—often in shattering prose—the contradictions and complexities at the heart of modern American culture. And Simone de Beauvoir because she was one of the smartest people of the 20th century, and one of my first heroines when I was a girl.