On the Trail of Jewish Books Through Centuries

Footprints are a perennial clue in detective stories, evidence at crime scenes, or a symbol of absence. One project at Columbia is employing the word in all of those contexts, as well as metaphorically, as it tracks the trail of lost Jewish books published over centuries.

Columbia’s Center for Teaching and Learning, along with University Libraries and several higher education partners, launched the “Footprints Project” in 2014, a crowdsourced online database that follows the journey of Jewish books printed in all languages from the invention of moveable type to 1800.

“The study of the Jewish book is the study of its people,” said Michelle Chesner, the Norman E. Alexander Librarian for Jewish Studies at Columbia, and the project’s codirector. “We believe the Footprints project will facilitate a new kind of research in the history of the Jewish book.”

Jews often took books with them as they traveled or were expelled from various lands. Following the books essentially traces the history of their owners. These peregrinations can also trace the spread of ideas, such as Jewish mysticism, or illustrate relationships between Jews, Muslims, and Christians. “Combining old books with new technology can potentially be game-changing,” Chesner said.

Collecting evidence from the path of a volume, one can find markings that relate to that book’s owners, booksellers, subscription lists, estate inventories, censor marks, and much else.

This project is the first in Jewish Studies to harness the fruits of a new approach to the history of the book, to tell a larger cultural history.

For example, Nofet Tsufim, a work on Hebrew rhetoric, was printed in Mantua in 1474-76, censored there, turned up in a library in Munich later in the 18th century, and was subsequently owned by a London bibliophile. The book was part of a collection held at the now-defunct Delmonico Hotel in New York City in the early 1950s and was sold at Sotheby’s in 2008 to an unknown bidder.

Important Jewish libraries such as the Bibliothek der Israelitische Kultusgemeinde in Vienna or the Jewish Theological Seminary in Breslau/ Wroclaw had their books stolen and scattered by the Nazis. It is impossible to reassemble such collections, but the Footprints database can track some books and virtually reconstruct the library.

The database can be synchronized with Google maps to visualize a book’s trajectory, and the code is publicly accessible. Elisheva Carlebach, the Salo Wittmayer Baron Professor of Jewish History, Culture and Society, a scholar who works in the field of book history in addition to other fields, is an advisory board member of the project. A chair of the Institute for Israel and Jewish Studies, she will make use of Footprints in a course she is teaching this fall on Jewish Book cultures.

“This project is the first in Jewish Studies to harness the fruits of a new approach to the history of the book, to tell a larger cultural history,” she said.

Image Carousel with 3 slides

A carousel is a rotating set of images. Use the previous and next buttons to change the displayed slide

-

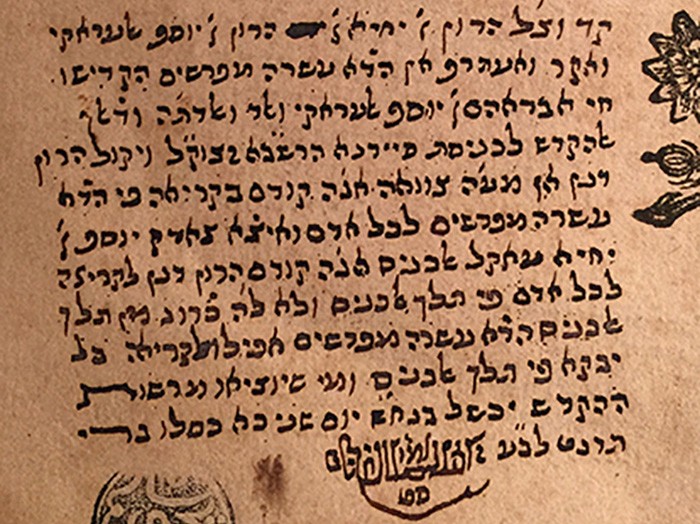

Slide 1: Inscription from Yosef Shohet indicating the circumstances under which he bought this book (published Berlin, 1725).

-

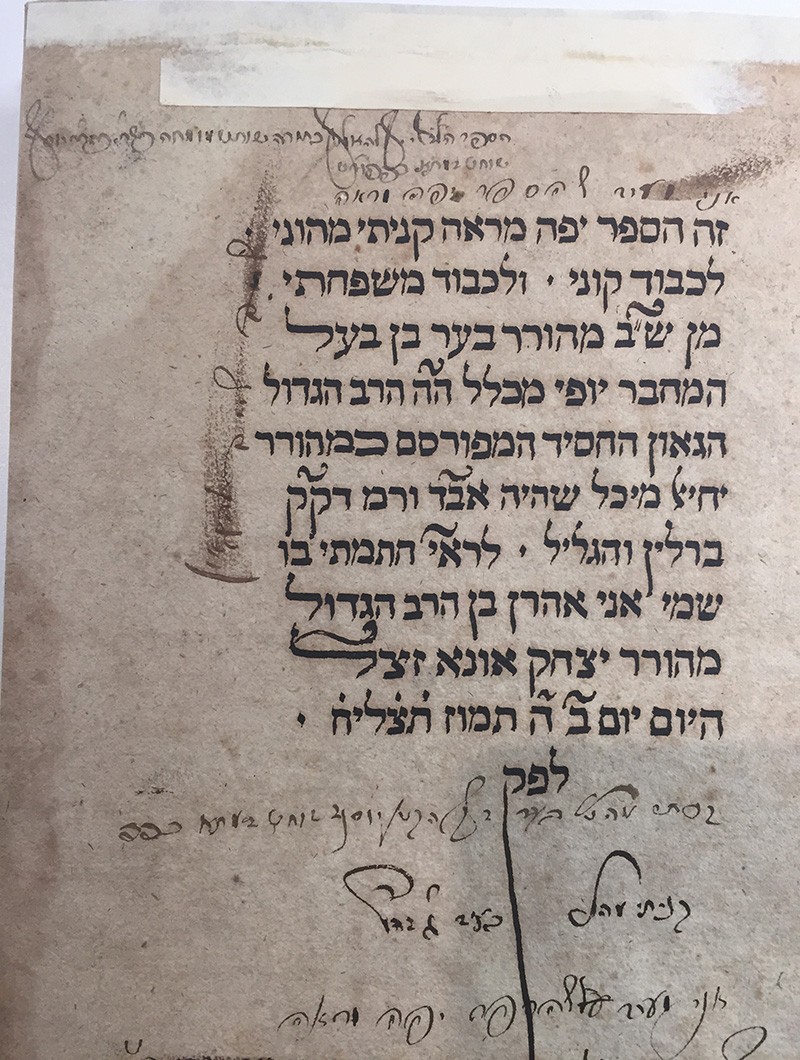

Slide 2: This is a Columbia book whose binding tells us the initials of one (or two) owners in 18th century Italy.

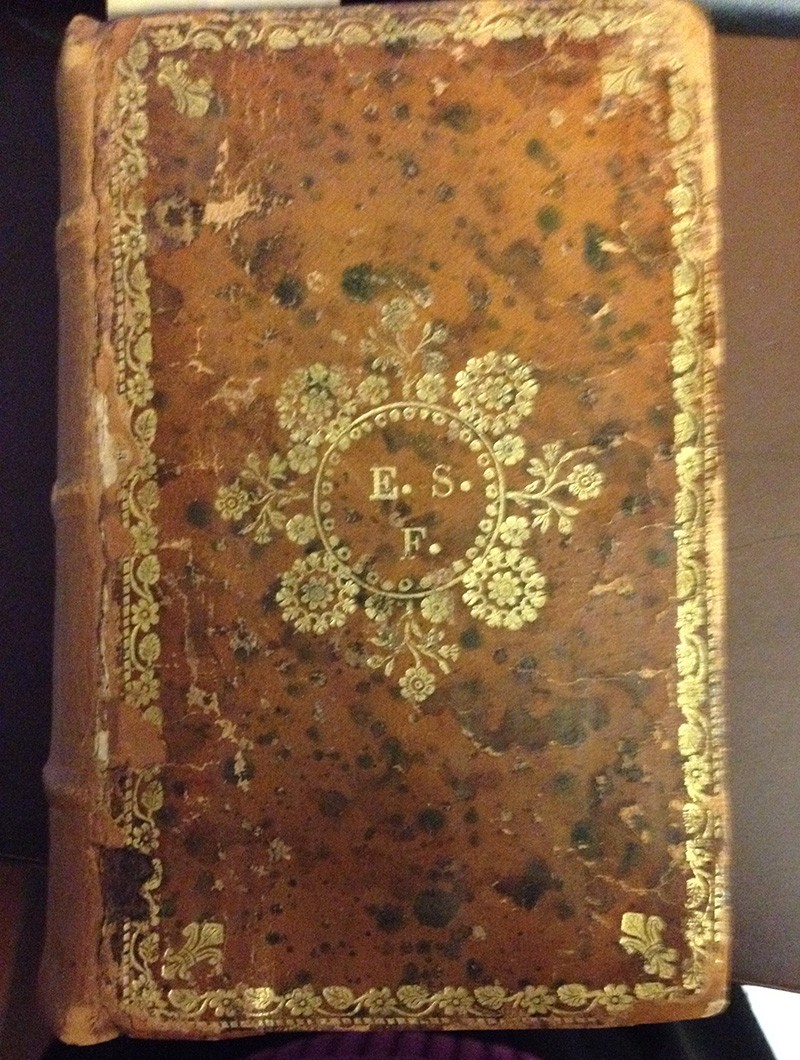

-

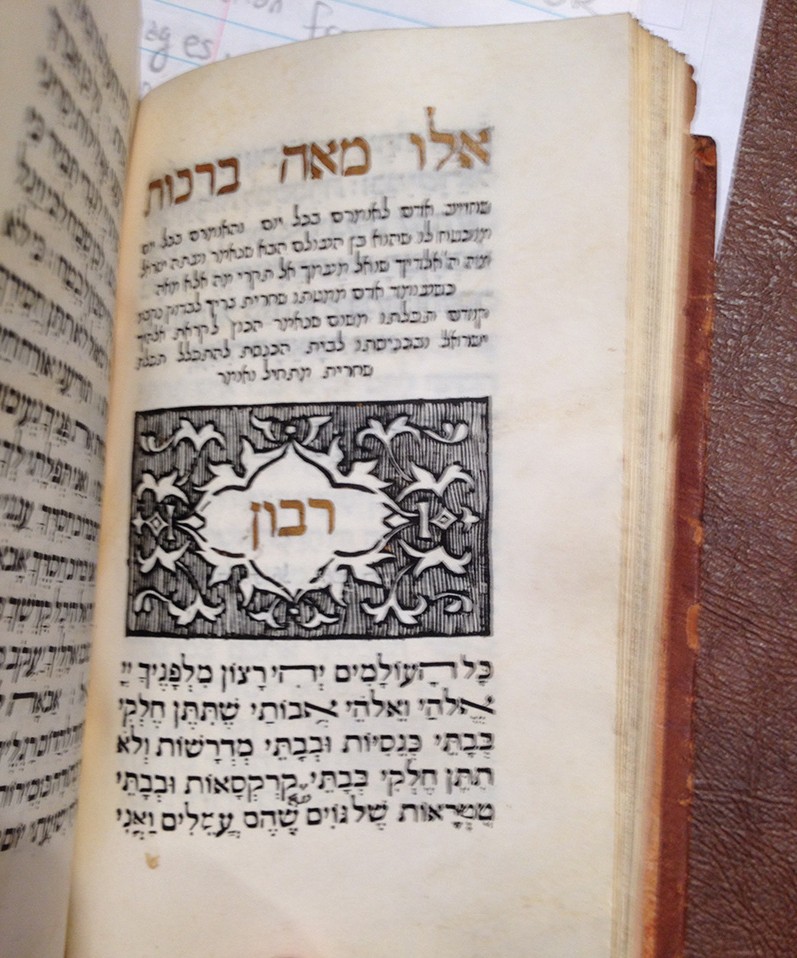

Slide 3: The Siddur was owned by one or two people in 18th century Italy.

Inscription from Yosef Shohet indicating the circumstances under which he bought this book (published Berlin, 1725).

This is a Columbia book whose binding tells us the initials of one (or two) owners in 18th century Italy.

The Siddur was owned by one or two people in 18th century Italy.

The project emerged four years ago from a working group at the Center for Jewish History in New York City, whose mandate was to follow the movements of certain important Jewish texts from the printing press to the hands of readers. When the group’s two-year term ended, it was clear further research was needed.

The technical infrastructure is under the direction of Kenny Hirschmann, senior learning designer at the Center for Teaching and Learning at Columbia, and by a number of engineers and developers. Its goal is to be a place where scholars can input and search data about the movement of the books.

One pivotal question is what exactly is a Jewish book? Is it defined by language? By topic? Most books in the project are Hebrew books by and for a Jewish audience, said Chesner.

She and her co-directors at the project’s partner schools at Jewish Theological Seminary, University of Pittsburgh and Stony Brook University encourage scholars, librarians, collectors and researchers to enter their own data. Working with scholars around the world, they now have more than 6,000 records on the site.

One example of a book’s unusual journey involves Columbia’s own copy of Arba’ah Turim, a work on Jewish law owned by a German rabbi and book collector, Jacob Emdem, who died in 1776. The British Library purchased half his books in 1862, and Temple Emanu-El in New York City bought the remainder a decade later.

In 1892, Richard James Horatio Gottheil, Professor of Rabbinic Literature at Columbia and the son of Temple Emanu-El's then-rabbi, arranged for the collection to be donated to the University.

Chesner is fascinated about the burn holes in the book. “Emden writes in one of his published works that he would often stay up late studying, and sometimes he would drift off and the candle would slip,” she said. “Books have a history that can tell stories beyond the text.”