Uncovering the Hidden Life of Martha Graham, Modern Dance Icon

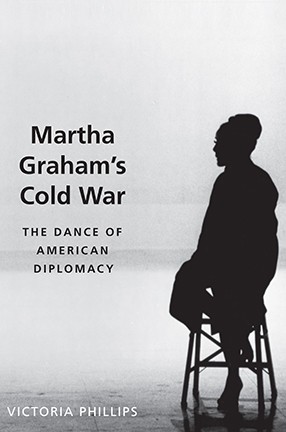

Historian Victoria Phillips examines the power of cultural diplomacy in her new book, Martha Graham's Cold War.

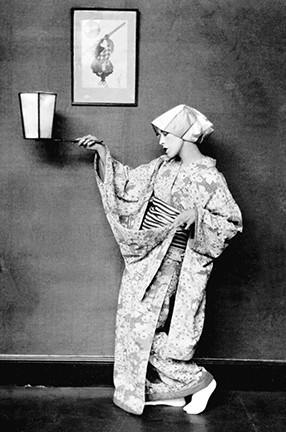

In 1955, Martha Graham, whom the press had dubbed the “High Priestess of Modern Dance in America,” began a U.S. State Department-sponsored tour of the “domino nations,” those countries considered most susceptible to communism. Graham, who famously claimed that she was “not political,” went on to perform with her company on five continents during the administrations of eight U.S. presidents. The congressional record shows that her charisma was electric at home and abroad, making her an important ambassador on the diplomatic “cocktail circuit.”

In her latest book, Martha Graham's Cold War: The Dance of American Diplomacy, historian Victoria Phillips examines Graham’s more than 30-year career, framing it as pro-Western Cold War propaganda that promoted American democracy. In choreography that focused on women protagonists whose stories promoted timeless politics and cultural values, Graham’s work demonstrated the power of the free world.

Columbia News recently spoke with Philips (GS’85, BUS’88, GSAS'08 and '13) about the book, her influences, and her teaching.

Q: How did your research help you redefine Martha Graham?

A: My fascination with the Depression era, Marxism and communism drew me to the interwar period in dance, which had not been much studied at that point except by a group of ground-breaking scholars. Having studied Graham technique with Bertram Ross at The New Dance Group in the 1970s, I was aware of their connection to the 1930s protest culture. The choreography addressed racism, hunger and housing. There were classes for children and adults with political improvisation, and performances were held in union houses and on the streets at rallies. I discovered in the New Dance Group’s archives that the dancers were linked to a network of radical, communist traveling artists. Graham’s history is a complex one fraught with drama if read in the context of women fighting the Cold War, as one sees Graham working with Clare Booth Luce, ambassador to Italy, Eleanor Dulles, sister of both the secretary of state and director of the CIA, and so forth. But why did she deny her role in the Cold War political and propagandistic context? Despite Graham declaring that her work was not political, there was plenty of evidence to the contrary: a 1936 letter from Goebbels, the Nazi propaganda minister, inviting her to perform in Berlin; an elaborate 1956 brochure on a summit to fight the communists in Asia, with an invitation for her to participate; and State Department reports on her and other invitations from politically powerful men asking her to perform or join official events.

Q: You were once a dancer. How did you find a path to become a historian?

A: When I was 16, I went to see the Martha Graham Dance Company and thought, “I want to do that.” I began classes at the Graham School and stayed until I turned 20. I entered the School of General Studies at Columbia full-time when I was 21, and directionless. The core curriculum was perfect for me. I had always loved to write, so I fell naturally into the literature and creative writing major, determined to become a novelist. As I was finishing my degree, I ran out of tuition money, so I went to work for Columbia Business School, scheduling rooms and student events. I also began sitting in on security analysis classes and found that I had an instinctive knack for fundamental analysis. Looking at an industry and company history, pulling apart numbers and letting them tell a story taught me to build investigative research skills critical to being a scholar. Through various twists and turns, none predictable or rational, I ended up taking a dance history course at Barnard with Lynn Garafola and that put me on a path to become a historian.

Q: Which three books have influenced you the most?

A: If I were to pick three books that influenced me the most as a historian, they are Victoria de Grazia’s Irresistible Empire, Stephen Kotkin’s Magnetic Mountain and Anders Stephenson’s Manifest Destiny. I’ve always wanted to write a book like Irresistible Empire: the analytical framework, the bones, the footnotes, the prose, the storytelling. When taking the dissertation to book, de Grazia’s research and footnotes were particularly helpful. I went back to the archives and looked at the photographs of the dancers on the tours, which were incorporated to illuminate the bones of my analysis on Graham. I have also been deeply inspired by Kotkin’s work. His approach to archives and narratives, and his footnotes always provide a rich underlayer to his work. You may disagree with a scholar or institutional approach on any given topic, but he taught me alongside Carol Gluck not to clutter the book with a disagreement. Do it in the footnotes. Lastly, Anders Stephenson has been a huge influence on my work. His book does exactly what I cannot: it tells the story briefly, concisely and to the point. My book is a bit longer than I wish it were.

Q. What can you tell us about your Cold War Archival Research Project?

A: At Columbia, with the backing of the European Institute, I started the Cold War Archival Research project (CWAR). Every year, I supervise eight to 10 undergraduate, M.A. and Ph.D. students, along with two cadets from West Point Military Academy, and recently students from the London School of Economics. They visit archives in the United States and Europe to explore new areas of Cold War cultural diplomacy. The CWAR fellows have gone into politics internationally, academia, finance, consulting, you name it. I am hoping to build a network of scholars, diplomats and leaders, who work together with the experienced knowledge across boundaries and ask the big questions. My work and the Martha Graham book would not be as rich without CWAR and its fellows. I learn every day, every semester, from my students. When I die, I want my tombstone to read “Fearlessly Curious.”

Image Carousel with 4 slides

A carousel is a rotating set of images. Use the previous and next buttons to change the displayed slide

-

Slide 1: Jacqueline Kennedy [Onassis] with Martha Graham at the Martha Graham Center of Contemporary Dance in New York. (c)Library of Congress.

-

Slide 2: Martha Graham and Henry Kissinger, with Nancy Kissinger and Alan Greenspan observing, Nov. 16, 1976. (c)Karl Schumacher | Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library and Museum.

-

Slide 3: Appalachian Spring with Rudolf Nureyev (Preacher), Terese Capucilli (Bride), Mikhail Baryshnikov (Husbandman) and Maxine Sherman (Pioneer Woman), October 6, 1987. (C)Robert R. McElroy | Associated Press.

-

Slide 4: Martha Graham with Betty Ford, Roy Halston, Elizabeth Taylor, and Liza Minelli outside Studio 54 at midnight, May 21, 1979. Ron Frehm | Associated Press.

![Jacqueline Kennedy [Onassis] with Martha Graham at the Martha Graham Center of Contemporary Dance in New York. (c)Library of Congress. Two women posing facing the camera](/sites/default/files/styles/cu_crop/public/content/19.Jackie.594x400.jpg?itok=OUzynjTH)

Jacqueline Kennedy [Onassis] with Martha Graham at the Martha Graham Center of Contemporary Dance in New York. (c)Library of Congress.

Martha Graham and Henry Kissinger, with Nancy Kissinger and Alan Greenspan observing, Nov. 16, 1976. (c)Karl Schumacher | Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library and Museum.

Appalachian Spring with Rudolf Nureyev (Preacher), Terese Capucilli (Bride), Mikhail Baryshnikov (Husbandman) and Maxine Sherman (Pioneer Woman), October 6, 1987. (C)Robert R. McElroy | Associated Press.

Martha Graham with Betty Ford, Roy Halston, Elizabeth Taylor, and Liza Minelli outside Studio 54 at midnight, May 21, 1979. Ron Frehm | Associated Press.

Q. Who are your dream guests, dead or alive, for a dinner party?

A: I would like several round tables of six, and guests would change seats by lottery with each course. A bit of musical chairs, but choreographed. It would be candle lit and elegant, black tie, although also relaxed. The food would be superb. Certainly the Roosevelts (Eleanor and Franklin) would be there, as would Nelson Rockefeller, Dwight D. Eisenhower, George Kennan, Eleanor Dulles, Betty Ford, Francis Mason, Noguchi, my orals and dissertation committees, my grandmother, my nanny, a few colleagues and close friends, some former students and fellows, my daughters and my husband. I would want Martha Graham there, too, but we would change seats regularly so that she would not dominate the entire table.