The University Is Right to Celebrate Indigenous Peoples' Day

This was—and is—an important step in dismantling the “Doctrine of Discovery” that has always plagued the U.S. legal system.

October 12th is almost here.

Last fall, Columbia University Senate passed a resolution officially recognizing Indigenous Peoples' Day to be celebrated on the second Monday of October every year. The students of the Native American Council had presented this proposal to the University leadership. This resolution, demonstrating their strength, perseverance, and vision, successfully concluded a mobilization of many years that also included faculty and other Columbia employees.

“Columbus Day” has been marked on calendars since 1937. Yet to celebrate the “discovery” of America is to celebrate a history of genocide, forced displacement, land-grabbing, systemic discrimination and the erasure of Indigenous Peoples. Efforts to rename Columbus Day go back to 1977, when the historic Conference of Indigenous Peoples of the Western Hemisphere was held at the United Nations in Geneva. Indigenous leaders had gathered in the context of the International Conference against Racial Discrimination. The conference recommended replacing Columbus Day and creating Indigenous Peoples' Day as an expression of solidarity with the Indigenous Peoples of the Americas. This was—and is—an important step in dismantling the “Doctrine of Discovery” that has always plagued the United States legal system. The continuing effects of colonization are clear today, as Indigenous Peoples work to regain their languages and respect for their lands, cultural heritage, and sovereignty amid poverty, unemployment, disproportionate exposure to COVID-19, and other grim social statistics.

Following mobilizations around the world over the last decades, especially since the adoption of the historic U.N. Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples in 2007, a growing number of states, cities, and institutions in the U.S. have adopted Indigenous Peoples' Day. These include Alaska; Vermont; Seattle, Wash.; Albuquerque, N.M.; Los Angeles, San Francisco, and Berkeley (the first to mark Indigenous Peoples' Day in 1992), Calif.; Denver, Colo.; Maine, New Mexico, Oregon, South Dakota and Cambridge, Mass.

In 2017, for the first time, Columbus, Ohio, chose not to observe the controversial federal holiday honoring its namesake. In recent years, both Harvard and Princeton have embraced Indigenous Peoples' Day.

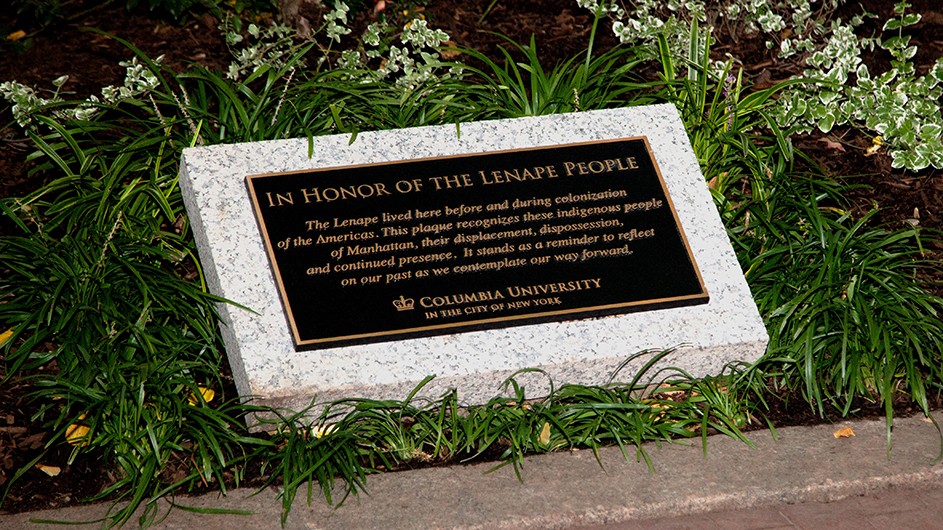

Four years ago, Columbia University proudly placed a plaque in the courtyard in front of John Jay Hall, recognizing that the campus was built on traditional Lenape territory. Like other major educational institutions, Columbia has a crucial role in raising awareness and educating not only students, but also the general public.

It’s time to rethink history, to practice ethical remembrance and to find ways to make amends with the full and effective participation of Indigenous Peoples. This year, Columbia honors and celebrates the cultural heritage, struggles, contributions, and continuing presence of the Indigenous Peoples. We live in times when, despite growing challenges to human rights and democracy, we can make a difference, we can create decolonized spaces and spaces of justice, here, where we live.

Elsa Stamatopoulou is the director of the Indigenous Peoples Rights Program at the Institute for the Study of Human Rights (ISHR) and an adjunct professor in anthropology at ISHR and the Center for the Study of Ethnicity and Race (CSER). ISHR has scheduled two events tied to Indigenous Peoples' Day: one on Indigenous Peoples of the Americas and the COVID-19 Pandemic and another on Indigenous Peoples’ Rights and Elections. This column is editorially independent of Columbia News.