Columbia Engineers Mine Big Data to Faster Assess Carbon Footprints

Researchers at Columbia Engineering have developed a new software that can simultaneously calculate the carbon footprints of thousands of products faster than ever before.

“Our novel approach generates standard-compliant product carbon footprints for companies with large portfolios at a fraction of previously required time and expertise,” says Christoph Meinrenken, the study’s lead author and associate research scientist at Columbia Engineering and The Earth Institute.

The study, recently published online in the "Journal of Industrial Ecology" and scheduled for the October 2012 print issue, is the result of a collaboration that began in 2007 between The Earth Institute, Columbia University, and PepsiCo, Inc. The collaboration’s original aim was to evaluate and help standardize product carbon footprinting and labeling in both the U.K, and the U.S. This resulted in the first ever certified product carbon footprint in the U.S., for Tropicana orange juice. The work, conducted at the Institute’s Lenfest Center for Sustainable Energy, was expanded in 2009, advancing from manual measurements to automated, big-data-supported footprint calculations, and PepsiCo has been successfully pilot-testing the methodology since summer 2011.

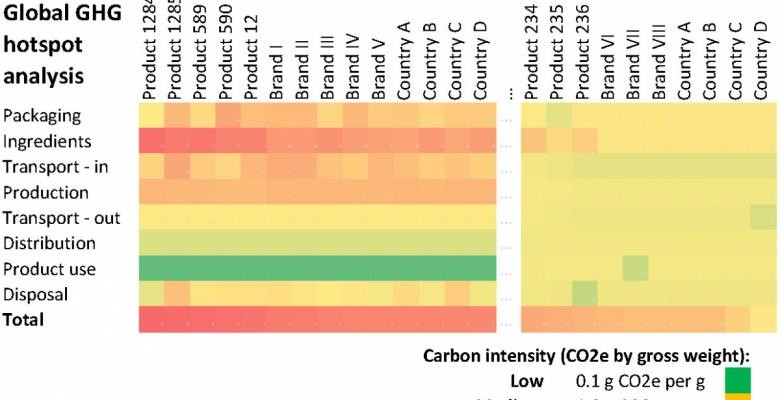

Meinrenken and his team used a life-cycle-analysis (LCA, a tool used to judge the environmental impact of a product) database that covered 1,137 individual products from PepsiCo. The researchers developed three new techniques that work in concert in a single approach, enabling them to calculate thousands of footprints within minutes and with minimal manual user input. The key component in the Columbia Engineering methodology is the design of a predictive model that generates estimated emission factors (EFs) for materials, thereby eliminating the manual mapping of a product’s ingredients and packaging materials to commercial LCA databases.

“These autogenerated EFs,” says Meinrenken, “enable non-LCA experts to calculate approximate carbon footprints and alleviate resource constraints for companies embarking on large-scale product carbon footprinting.”

The software complies with the latest product LCA guidelines sponsored by the World Resources Institute, and any carbon footprint it calculates can easily be audited against this standard, he said.

Up until now, companies trying to carbon footprint their entire range of products, such as Tesco in the U.K., have faced major obstacles—mostly enormous requirements on personnel, expertise, and in the time it takes to collect and analyze all necessary data. That’s because life-cycle-analysis has traditionally been performed manually, one product at a time, and so carbon footprinting large portfolios of many distinct products and services has proven very resource-intensive. Most companies do not have the manpower to focus massive numbers of personnel on the task, especially since it requires extensive, specialized LCA expertise. As a result, quantifying carbon footprints for the often hundreds or thousands of individual products of globally operating companies has essentially been impossible. Meinrenken notes that while some companies have tried to overcome this bottleneck by reverting to aggregate data and calculations, they usually miss out on the very microscopic level of detail that proper LCA offers. This can cause compliance issues with international footprinting standards.

As is often the case in interdisciplinary engineering, the Columbia Engineering team’s approach to LCA was actually inspired by fields outside of environmental science. Meinrenken observes: “Many companies nowadays have an ever-increasing amount of data available to them but have scarce resources to actually manage and intelligently analyze this raw data into actionable information. In contrast, at companies like Facebook or Netflix, engineers employ statistical wizardry to mine these vast datasets and essentially teach computers to predict, for instance, who will like a particular movie.”

So Meinrenken devised some wizardry of his own—a tool to mine companies’ detailed product and supply chain data into environmentally meaningful information.

“For an environmental engineer,” he says, “using such data to estimate how much the environment will ‘like’ certain products and services is especially rewarding. Mining all the ‘big data’ that’s already available in companies' data warehouses will enable us to calculate the carbon footprints of thousands of products virtually simultaneously.”

This automated information can help companies speed up their assessments of the impact of reduction strategies, such as using less carbon-intensive fertilizers when making orange juice, as PepsiCo has already discovered.

Companies won’t be the only ones benefitting from this new approach.

“Consumers will be able to make more informed choices when selecting products to buy,” adds Meinrenken. “And environmental advocacy organizations can be supplied with the latest, up-to-date environmental impact data. It’s really a win-win for all.”

“This is exciting work,” says Klaus Lackner, Maurice Ewing and J. Lamar Worzel Professor of Geophysics in the department of Earth and Environmental Engineering and director of The Earth Institute’s Lenfest Center for Sustainable Energy, who has led the LCA research with PepsiCo since 2007. “Fast carbon footprinting is a great example of how academic methodologies like LCA, when coupled with modern data processing and statistical tools, can be brought to life and unlock their power in the real world.”

Meinrenken notes that widespread use of his technique will increase its accuracy, as more usage data will allow his research team to improve the calibrations of their algorithms.

“We are continuing our collaboration with PepsiCo,” he says, “and plan to make some of the underlying methodology and software available to other large companies who are active in the LCA arena.”

PepsiCo is currently using the Columbia Engineering methodology to evaluate sustainability aspects and possible impact reduction strategies of entire product lines.

“As part of our ‘Performance with Purpose’ strategy, PepsiCo has a long-standing relationship with Columbia’s Earth Institute to help promote innovative solutions that support business and environmental objectives,” said Al Halvorsen, Senior Director of Sustainability at PepsiCo. “The newly developed software promises to not only save time and money for companies like PepsiCo, but also to provide fresh insights into how companies measure, manage, and reduce their carbon footprint in the future.”

Meinrenken’s team is looking at transferring this methodology from carbon to other LCA aspects such as water use.

“We designed the core methodology to be transferrable to other environmental impacts besides carbon,” he adds, “but we are looking for real life datasets to fine tune some of the details.”