You've Heard of Water Droughts. Could 'Energy' Droughts Be Next?

In a new modeling study, researchers show how widely wind and solar potential vary by season and year.

Renewable energy prices have fallen by more than 70 percent in the last decade, driving more Americans to abandon fossil fuels for greener, less-polluting energy sources. But as wind and solar power continue to make inroads, grid operators may have to plan for large swings in availability.

The warning comes from Upmanu Lall, a professor at Columbia Engineering and the Columbia Climate School who has recently turned his sights from sustainable water use to sustainable renewables in the push toward net-zero carbon emissions.

"Designers of renewable energy systems will need to pay attention to changing wind and solar patterns over weeks, months, and years, the way water managers do,” he said. “You won’t be able to manage variability like this with batteries. You’ll need more capacity."

Patterns, March 11, 2022

In a new modeling study in the journal Patterns, Lall and Columbia PhD student Yash Amonkar, show that solar and wind potential vary widely over days and weeks, not to mention months to years. They focused on Texas, which leads the country in generating electricity from wind power and is the fifth-largest solar producer. Texas also boasts a self-contained grid that’s as big as many countries’, said Lall, making it an ideal laboratory for charting the promise and peril of renewable energy systems.

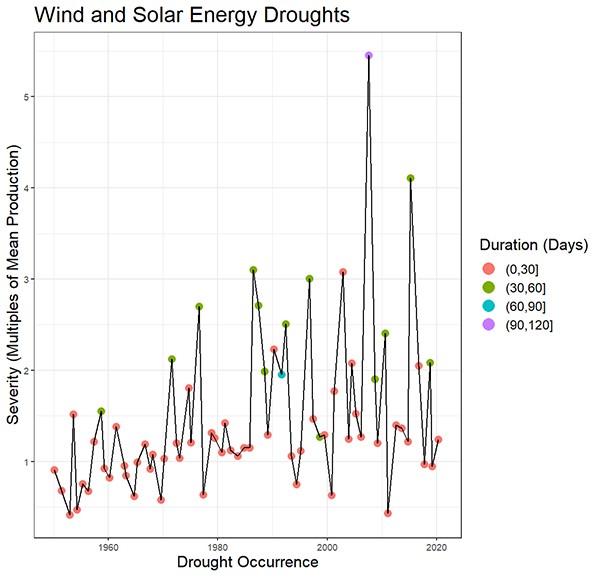

Drawing on 70 years of historic wind and solar-power data, the researchers built an AI model to predict the probability of a network-scale "drought," when daily production of renewables fell below a target threshold. Under a threshold set at the 30th percentile, when roughly a third of all days are low-production days, the researchers found that Texas could face a daily energy drought for up to four months straight.

Batteries would be unable to compensate for a drought of this length, said Lall, and if the system relied on solar energy alone, the drought could be expected to last twice as long—for eight months. “These findings suggest that energy planners will have to consider alternate ways of storing or generating electricity, or dramatically increasing the capacity of their renewable systems,” he said.

Anticipating Future ‘Energy’ Droughts—in Texas, and Across the Continental United States

The research began six years ago, when Lall and a former graduate student, David Farnham, examined wind and solar variability at eight U.S. airports, where weather records tend to be longer and more detailed. They wanted to see how much variation could be expected under a hypothetical 100% renewable-energy grid.

The results, which Farnham published in his PhD thesis, weren’t a surprise. Farnham and Lall found that solar and wind potential, like rainfall, is highly variable based on the time of year and the place where wind turbines and solar panels have been sited. Across eight cities, they found that renewable energy potential rose and fell from the long-term average by as much as a third in some seasons.

“We coined the term ‘energy’ droughts since a 10-year cycle with this much variation from the long-term average would be seen as a major drought,” said Lall. “That was the beginning of the energy drought work.”

In the current study, Lall chose to zoom in on Texas, a state well-endowed with both sun and wind. Lall and Amonkar found that persistent renewable energy droughts could last as long as a year even if solar and wind generators were spread across the entire state. The conclusion, Lall said, is that renewables face a storage problem that can only realistically be solved by adding additional capacity or sources of energy.

“In a fully renewable world, we would need to develop nuclear fuel or hydrogen fuel, or carbon recycling, or add much more capacity for generating renewables, if we want to avoid burning fossil fuels,” he said.

In times of low rainfall, water managers keep fresh water flowing through the spigot by tapping municipal reservoirs or underground aquifers. Solar and wind energy systems have no equivalent backup. The batteries used to store excess solar and wind power on exceptionally bright and gusty days hold a charge for only a few hours, and at most, a few days. Hydropower plants provide a potential buffer, said Lall, but not for long enough to carry the system through an extended dry spell of intermittent sun and wind.

“We won’t solve the problem by building a larger network,” he said. “Electric grid operators have a target of 99.99% reliability while water managers strive for 90 percent reliability. You can see what a challenging game this will be for the energy industry, and just how valuable seasonal and longer forecasts could be.”

In the next phase of research, Lall will work with Columbia Engineering professors Vijay Modi and Bolun Xu to see if they can predict both energy droughts and "floods," when the system generates a surplus of renewables. Armed with these projections, they hope to predict the rise and fall of energy prices.