The Story Behind the Standing Memorial to September 11 on Columbia’s Campus

On the northeast corner of Low Library sits a low-profile 9/11 memorial to members of the Columbia Business School community. How did that memorial come to be?

Phidia Wong (BUS’01) had just graduated from Columbia Business School in the spring of 2001, landing a prestigious job in the investment banking division of Citigroup in Hong Kong. On the morning of September 11, 2001 she boarded the 1 train from her residence on West 26th Street and headed toward the World Trade Center with 16 of her colleagues, destined to attend training at the center of New York's business community at 7 World Trade Center. They were on the train when the first plane hit 1 World Trade Center.

The train slowed, then stopped, and Wong was ushered out of the Chambers St. station into chaos. While walking with her colleagues, Wong was trying frantically to call a friend who worked in the World Trade Center to make sure she was alright. That’s the last thing she remembers before being hit by some kind of debris as the second plane hit 2 World Trade Center.

RELATED CONTENT

Wong was transported to Bellevue Hospital by a paramedic. She suffered from multiple injuries and fractures including her back, sternum, pelvis, and eye socket, etc. Doctors weren’t sure if she’d fully recover.

“I was very lucky,” Wong said in a recent call about the 20th anniversary of the September 11 attacks. “There was only one other victim I knew from the hospital who was seriously injured, but didn’t die. You just feel it all. I kept thinking: “Why is the world like this?” I was very scared. My bed in the hospital was by the window. One day, I saw a helicopter departing close to me. I remember screaming for help, that the terrorists are coming again.”

She stayed in the hospital for two months while a metal rod was inserted in her spine and she was eventually able to leave New York City in December 2001 to return to her homeland of Hong Kong. Over the years she was able to make a gradual and decent recovery.

The Impact on the Columbia Business Community

Wong is just one of hundreds of Columbians who were affected by the attacks on September 11. Indeed, 42 Columbians died that day. But Wong’s story also illustrates something else important: the incredible impact that September 11 had on Columbia Business School, which lost 10 alumni in the attacks, and many others were injured.

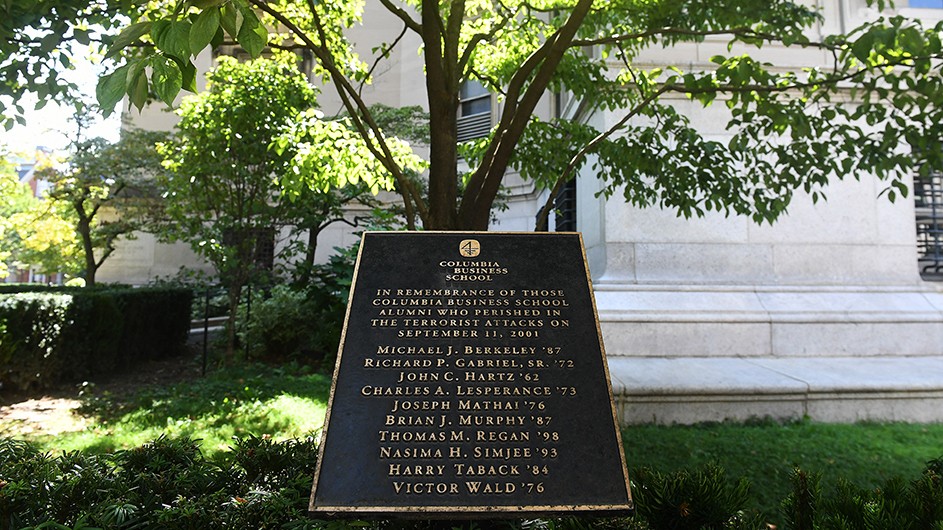

In fact, the only standing memorial to the victims of the September 11 attacks on Columbia’s campus is a testament to those alumni who were lost. If you were to walk to the center of campus, near the northeast corner of Low Library across the lawn from Uris Hall (where the Business School is currently located), you’d find the monument under a shaded tree reading:

In remembrance of those Columbia Business School Alumni Who Perished in the Terrorist Attacks on September 11, 2001:

Michael J. Berkeley, ‘87

Richard P Gabriel, Sr., ‘72

John C. Hartz, ‘62

Charles A. Lesperance, ‘73,

Joseph Mathai, ‘76

Brian J. Murphy, ‘87

Thomas M. Regan, ‘98

Nasima H. Simjee, ‘93

Harry Taback, ‘84

Victor Wald, ‘76

How Did the Memorial Come to Be?

Jace Schinderman, former associate dean at Columbia Business School under Dean Meyer Feldberg’s administration, remembers the morning of September 11 as “a spectacularly blue day, the kind of day we were born for.”

It was early in the morning when Schinderman heard the beginnings of commotion in the Business School lobby and saw 10-15 people watching the televisions installed there.

“Nobody was watching the ticker tape, they were watching the plane that had seemingly flown into 1 World Trade Center by accident,” Schinderman said.

She went to grab Dean Feldberg by the time some 200 students had gathered in the lobby.

“At the moment it was eerily quiet,” Feldberg remembers. “People could not believe what they were seeing. But suddenly everyone started weeping and crying.”

By 11 a.m., some 600 or 700 students had gathered in the lobby and Dean Feldberg and Schinderman were traversing the floors of Columbia Business School checking on employees and students alike, beginning to put together a list of Columbians they knew who worked in the towers.

“It was a family,” Feldberg said.

Danny Mayer (BUS’02) was one of those hundreds of students in the lobby that day. As president of the Graduate Business Association (GBA), he remembers meeting with his administration and that one of his teammates was visibly concerned that her husband was supposed to be down near the towers.

“I learned that you have to take care of your internal team first,” Mayer said.

Mayer met with the dean and tried to figure out what GBA could do to help.

“They said, we have to figure out what our resources are,” Mayer said. “We had to make sure we had bottles of water and that we were keeping track of who was impacted. We had a ton of people in those towers.”

It was during that time that the Business School opened its doors to office workers fleeing lower Manhattan, trying to make their way home to New Jersey and Westchester even as transit had shut down.

“The dean sent the entire operations department to Broadway to buy up all the crates of coffee and bagels and cream cheese,” Schinderman said. “We opened the Hepburn Lounge. The rest of the day, alumni streamed in on their way home, walking across the bridge. They were just stunned.”

While Thursday and Friday of that week were a blur, by Monday, Schinderman remembers a yellow notepad that appeared on Dean Feldberg’s desk. It was a list of all the Columbian Business School people who were in the towers. As cell towers started working again and people were able to make contact with their families, Dean Feldberg would make ticks by people who were accounted for. By mid-week, it became clear that 10 names were still on the list as unaccounted for.

That’s when Mayer offered up an idea that he and his vice president Dustin Longstreth had thought of when trying to figure out how the student body could help.

“We had a conversation with the dean about making a memorial and he said we should make it happen,” Mayer said. “We had no idea how we’d get the money because it wasn’t in the budget, but when we contacted the plaque-making company and they found out it was for September 11, they donated it.”

Similarly, Mayer didn’t know where the plaque could go. But by circumstance, he ran into a member of Facilities who had a place where they needed to plant a tree. Mayer asked if they could plant the tree and place the plaque in honor of the victims of September 11. Facilities responded immediately: “We’ll take care of it.”

On May 9, 2002, the plaque and tree were dedicated next to an American dogwood tree in full bloom. The names of the 10 members of the Columbia Business School community who perished were read and honored in a ceremony that nearly 100 people attended.

“I would say that September 11 was a defining moment for everybody who went to school there at that time,” Mayer said. “We all remember where we were that day and who was lost. We had so many people impacted from every corner of the school.”

Finding Closure

As for Phidia Wong, she vividly remembers when Schinderman came to visit her in Bellevue in the days after September 11 before flight paths were reopened and her mother was able to come to New York to be with her.

“Jace has always been so sweet and good,” Wong says. “She was very kind to me and still writes me throughout the years."

After recovering for a few months, Wong went back to work with Citigroup in Hong Kong for about a year. She later realized she needed more time to mentally recover and figure out what she wanted to do with her life.

“There was this voice telling me constantly that 3,000 people died and you survived and it wasn’t a good feeling," Wong said. "I suffered from immense survivor’s guilt for a long time."

Her recovery changed after coming across Eckhart Tolle’s The Power of Now, which helped her live more in the moment rather than being in the shadow of the past. Today, she works happily for a private investor in Hong Kong.

“I just feel very blessed,” Wong said. “I don’t want to make it sound like September 11 is a good thing but because of it, I was able to see things differently than I otherwise would have. Sometimes people get the chance to awaken through tragedy. Maybe that is my case. In a way, I appreciate that.”